San Quentin State Prison: California's First Penitentiary

Ep. #4--Prison-Industrial Complex, Part I

Few prisons have such a prominent stature in pop culture and entertainment as the maximum-security penitentiary on the San Francisco Bay, San Quentin State Prison; and perhaps that’s because the state of California has been such a driving force in the entertainment business with counterculture figures like Johnny Cash placing the brutal walls of this fortress into the lexicon of American criminal lore. And boy, does America love our criminals: some of the most infamous train-robbers, murderers, cult figures, record producers, and literary icons—both men and women, both housed and put to death here (although myriad more men than the finer sex)—and to chart the prison’s history is to follow the path of both America and California’s history, as well as criminality in the sociological sense.

The earliest era of the San Francisco Bay has now become legendary because it was incredibly wild and violent—the ol’ Wild West was, in fact, just that… wild—and this incredibly populace, beautiful city was once a dusty outpost so far from civilization that mail took months and months to get there before the Pony Express, and then eventually the telegraph condensed space and time until we have arrived at this much more “civilized” time in modern history.

The ‘49ers

The Brittanica entry for the “Gold Rush of 1849,” tells us the following about the early settlers that came to this area on the West Coast—to seek their fortune, their version of the American Dream:

On January 24, 1848 a New Jersey prospector James Marshall discovered gold on the American River in northern California, while he was working on a sawmill owned by John Sutter. When news of the discovery leaked out, there was a mass migration to California, and in subsequent years a fortune in gold was mined.

These early settlers are paramount to the rough-and-tumble epic we’re about to tell; and although the story of humanity started long before European settlers arrived in Northern California, for the purposes of our story, we begin in 1851, just after the Mexican-American War.

This was when the Republic of California was welcomed into the union (i.e. 1850 anno domini to be exact). Remember that the United States had just fleeced the Mexicans for a huge chunk of real estate encompassing much of the modern-day Southwestern U.S., which up until that time hadn’t been properly settled by the Spaniards.

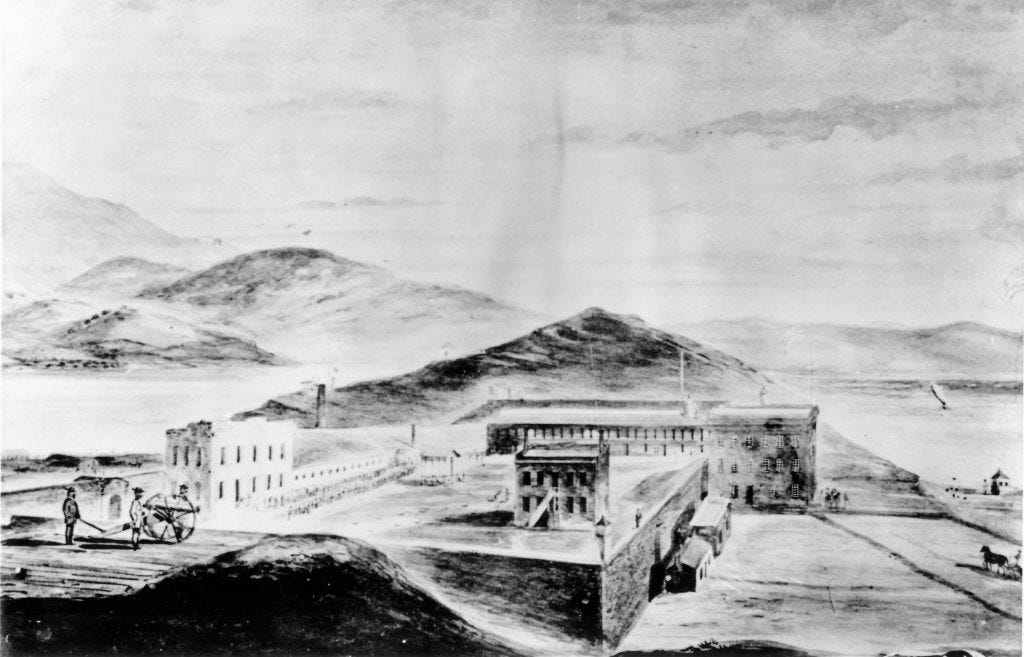

The massive state had nary a penal colony in a vast territory that was mostly bereft of settlement; and despite Spanish habitation, the majority of the state was largely unexplored wilderness with a system of missions and presidios mostly along the coast. They desperately needed a prison to hold their rough and rowdy, to scare up a little organized industry on behalf of the state—they badly needed forced labor to create a lot of the early works in the area—and as it was in antebellum America, they needed to execute the people who had a date with the hangman.

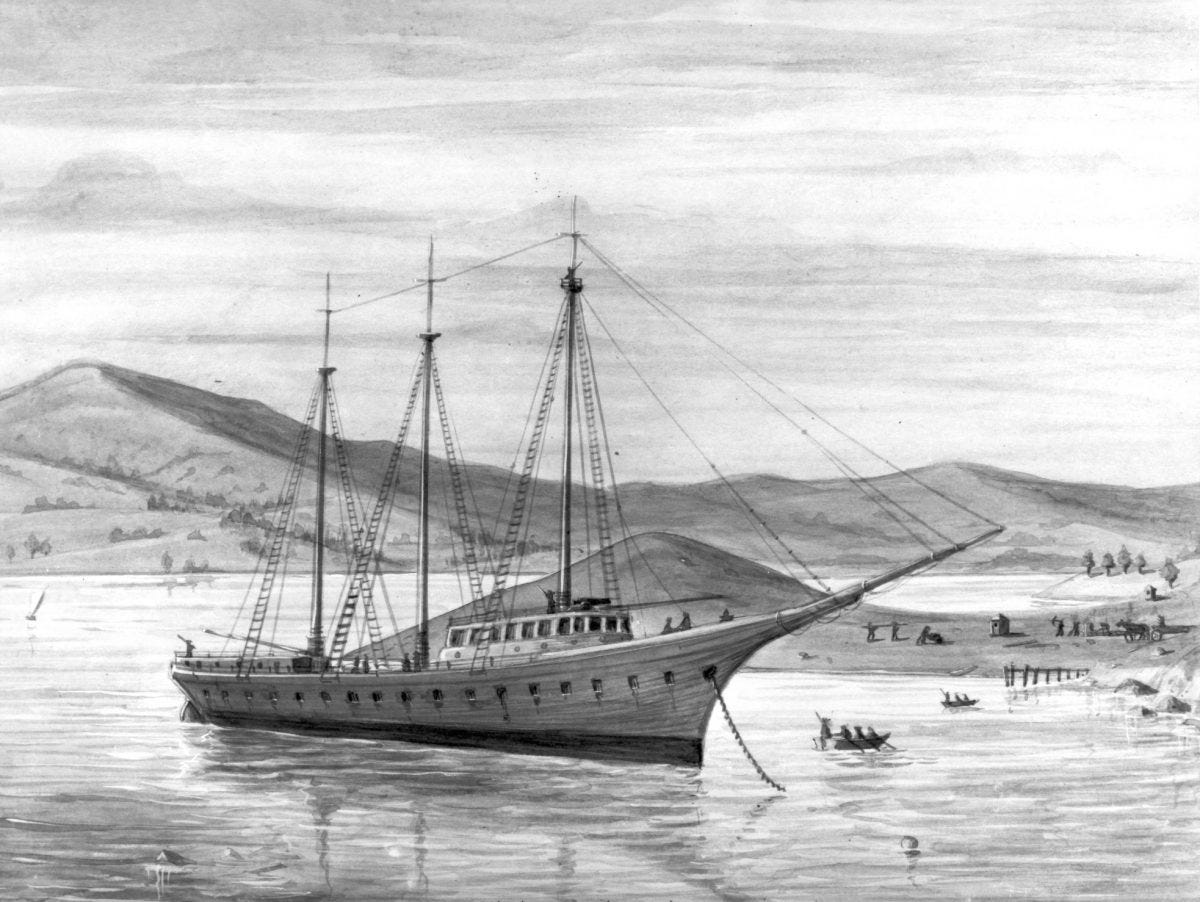

Waban

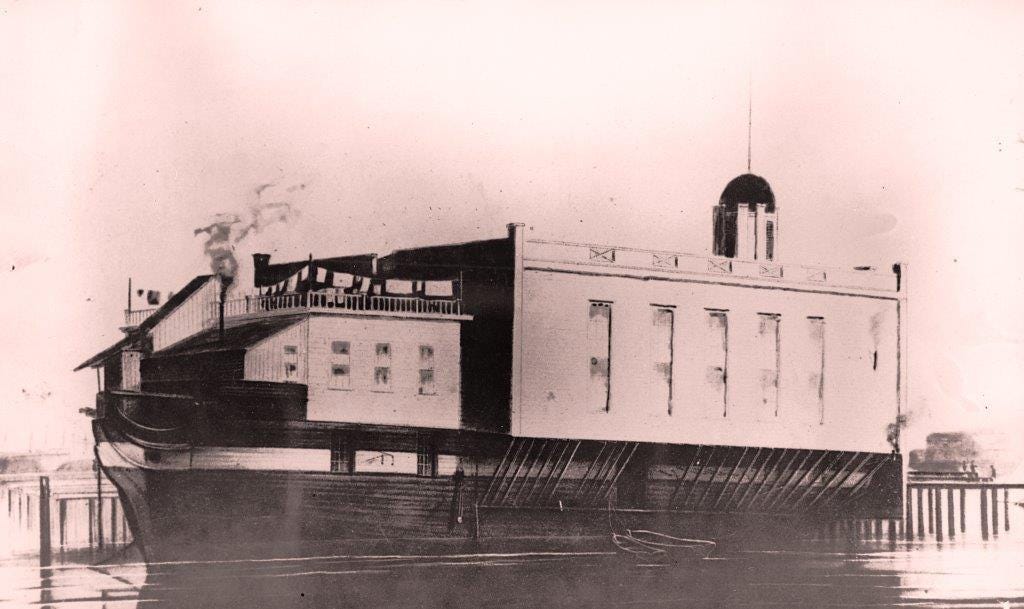

… And out of the sultry fog of the San Francisco Bay, a mysterious Spanish sloop entered the harbor to serve as California’s first prison. This was a common practice, and housing people on prison-ships goes back to the colonial era when any fortification on the mainland would be a military installation. There was a fort on nearby Alcatraz Island, so that was prioritized in development during that time, so San Quentin in its early conception was a floating slave’s galley like the British had during the Revolution.

Before the prison came ashore, it was a 68-ton wooden ship named the Waban with a dropped anchor in the bay; and it was to be outfitted so it could hold 30 inmates but ended up holding more than twice that many. As it is today, overpopulation was a problem immediately upon being built; and the earlier seaborne penal colony was no exception.

Across the massive state, there were only 16 counties at the time, and many of them were not equipped to ship prisoners up to the facility. The Sacramento jail was a floating fortress much like the Waban for years, and most of the inland areas were completely uninhabited. These frontier days were an outlaw’s heaven, and San Quentin was no different.

One must remember that jurisprudence and due process would result in a hanging for quite a few offenses; and that wasn't just because the 19th century was brutal and harsh for criminals. Think about the purpose and utility of keeping men locked up—there really isn’t much use for it, not then or now (able-bodied men should be doing something productive for society). Before the industrial age in an agrarian society, you wouldn’t want to limit the labor-pool in an area; and there was always the lingering danger of, ‘What do we do if there’s a riot or disturbance… can we stop these men if there’s a mutiny?’

If things went wrong at San Quentin—there were several such instances, full-blown riots—the corrections officers could only look to the army on Alcatraz Island to relieve them in an emergency.

Point San Quentin

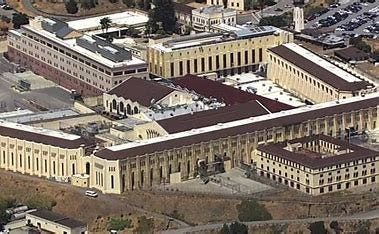

The facility sits on Point San Quentin—the geographical feature protruding into the waters where San Francisco Bay passes into San Pablo Bay—giving the inmates who’ve stood in these prison yards one of the best views of San Francisco, a beautiful cityscape on the horizon. People forget how large the Bay Area is, as this sprawling penitentiary consists of 432 acres (1.75 sq. km.); and if you had no idea that this was San Quentin behind the fog, you might think it was a university or library from the spectacular architecture and “open” concept.

Everything else has been developed and gentrified and rebuilt since the Great Fire of 1851—a year before the Waban came to shore—then again, during the Great Earthquake of 1906, somehow Point San Quentin is frozen in time. Of the 432-acre slice of expensive Bay Area real estate allotted to this penal colony, the prison complex itself occupies 275 acres (1.11 sq. km.). Everywhere else in San Fran is, and has gone to hell in the past… yet San Quentin with its convict residents is like an Ivory Tower in the fog.

“Why can’t we just move these people somewhere else?” has been the cry over the years. It doesn’t sit right with people that the scumbags inside SQ are given this beautiful view, this primo real estate, for the specifically horrific things they’ve done in earning their seat in hell.

But even though there have been calls to redevelop the aging prison, it’s clear the prison won’t be relocated because a) the state needs the bed-space; b) the prison is a historical monument; and c) the part this institution plays in the larger system is all too important for the safety of Californians.

‘Overpopulation Is a Feature…’

Overpopulation has always been a problem in American prisons, and maximum-security facilities are the most valuable type of prison within the larger system. The massive parapets walling in the savage criminals are almost beautiful, but even more terrifying. States aren’t building anymore of these relics, but rather choosing to create concertina-wired mausoleums of security-glass and stainless steel. They call doing time in one of these old-school penitentiaries, “Behind the wall,” because you’re literally behind a massive stone barrier like a fortress out of the Middle Ages.

Some of the Waban’s timber remains in part of the newer hospital structure inside the prison, by the way. And some of the older parts of the building are historical treasures of early California. To look at the building as its persisted in the rough climate of the Bay, it’s really an austere beauty with a Spanish colonial aesthetic. If the state of California wanted to get rid of the monstrosity, it’d be impossible to do so for the historic importance it holds, as well as its utility for the citizens writ large.

After a series of speculative land transactions and a legislative scandal, the 62 inmates who were housed on the Waban were move into a newly constructed prison on the north shore of the natural enclave.

As it stands today, SQ is home to California’s ill-used or neglected Condemned Unit, or “Death Row,” as it’s colloquially called. San Quentin State Prison is still an extremely violent prison that holds well over 3,200 inmates as of the last census in July 2022; and because it’s got multiple units, it’s what’s referred to as a ‘correctional complex…’

SUBSCRIBE HERE FOR FREE & ON APPLE PODCASTS FOR MORE OF THIS EPIC STORY—‘How San Quentin State Prison came to be as the oldest state-built, state-funded “public work” in California…’

Cited Works

Fimrite, Peter (20 November 2005). "Inside death row. At San Quentin, 647 condemned killers wait to die in the most populous execution antechamber in the United States". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2 July 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

“San Quentin: Inside CDRC”. Photo Timeline: San Quentin State Prison - Inside CDCR (ca.gov)

“Inside San Quentin”. National Geographic. 2006.

“San Quentin State Prison”. Wikipedia.

“San Quentin”. Documentary. 1974.

San Quentin historic murals launched artist's career - Inside CDCR